Is Your Pick and Place Machine Helping or Holding You Back?

- Introduction: What agile development looks like and why pick and place tool choice matters

- Status quo: Why many pick and place solutions fail to deliver

- Agile imperative: Engineers should only focus on high-value tasks

- Core criteria for a truly helpful pick and place machine

- Conclusion: Tools as enablers of agile hardware development

Introduction: What agile development looks like and why pick and place tool choice matters

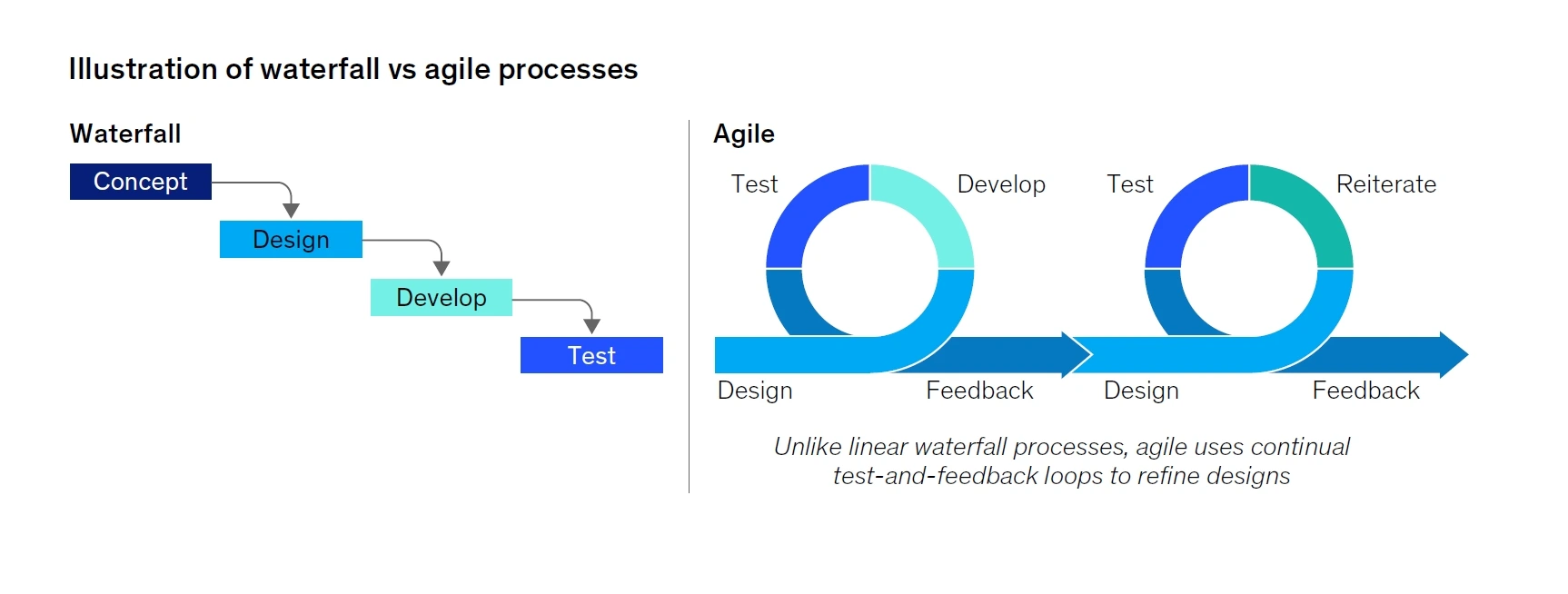

Traditional hardware development follows a linear “waterfall” path — from concept to design, build, test, and launch. This rigid model can frustrate engineers and drive up cost significantly, because by the time products reach market, customer needs may have shifted.

Alternatively, more hardware teams are adopting an agile approach, which breaks work into shorter cycles of “design → build → test → learn → iterate” rather than waiting for a monolithic prototype at the end. According to a McKinsey study, this gives teams on average 30% faster time-to-market, and 20% increase in product quality.

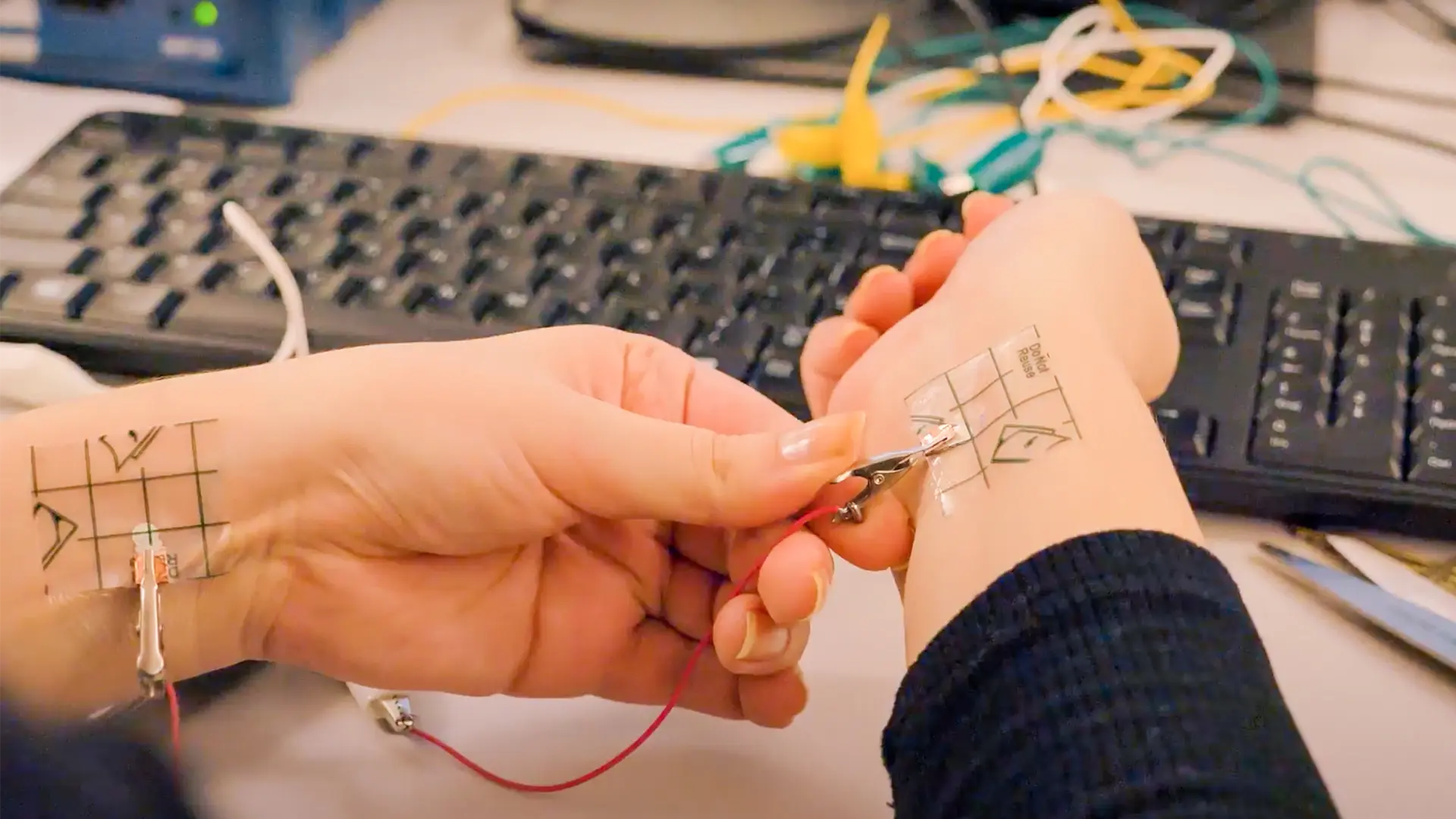

In the context of electronics prototyping, this means building multiple small batches of PCB assembly (PCBA), validating them, learning, and then refining. The faster you can iterate, the more experiments you can run, and the stronger your final product will be.

But agility in hardware is fragile. One misstep, like choosing the wrong assembly solution, can derail the entire rhythm. This is where tool choice becomes strategic. If your in-house pick and place (PnP) solution is slow to set up, imprecise, or requires constant rework, your agile loop will break.

Status quo: Why many pick and place solutions fail to deliver

Many teams are bringing PCB assembly in-house to avoid the unpredictable delays of outsourcing. Yet in practice, many pick and place machines still end up limiting agility. Here are some of the most common failure modes.

Long setup and calibration overheads

Currently in the market, pick and place robots are often made to achieve high-volume throughput, among which the industrial-grade pick and place systems can place tens of thousands components in an hour.

The trade-off lies in simply getting the machine running. Teams often spend hours on programming, calibrating tool heads, loading components into feeders, and fine-tuning vision systems before a single run. While such extensive setup can be justified in mass production, it rarely makes sense for small prototype volumes. In fact, this was a recurring theme among engineers during our market research. As one respondent noted:

“If it takes 5 hours to set up a pick and place machine only for a 10-minute run, it’s not worth it.”

This mismatch is a key reason many agile teams turn to outsourcing or manual assembly, both of which introduce longer lead times or higher error rates.

Disjointed workflow: Separate placement, soldering, and inspection

Many prototype workflows weave between separate tools: one machine for placement, another for soldering, and yet another for inspection. Each handoff introduces waiting times, increases the risk of human error, and often leads to costly rework.

These fragmented tools don’t just disrupt workflows, they also drive up upfront equipment costs and ongoing maintenance overhead. More importantly, they dictate how engineers are forced to operate. They conflict with agile’s core principle of valuing “individuals and interactions over processes and tools,” where people and collaboration should guide the workflow, not rigid, disconnected systems.

Accuracy and repeatability defects

Older or lower-cost pick and place machines often struggle to maintain consistent placement accuracy, leading to misalignments, tombstoning, or bridging, particularly in fine-pitch designs. Defects may stem from calibration drift, feeder inconsistencies, weak vision systems, or simply the machine being poorly built, all of which compound placement errors over multiple runs. Each unexpected assembly error forces engineers to either wait for repairs or rework boards manually, both outcomes that erase the benefits of rapid iteration.

These common reasons combine to turn a seemingly “fast” machine into a bottleneck. They force engineers to spend hours on operational battles rather than validating design ideas.

Agile imperative: Engineers should only focus on high-value tasks

One of the unfair burdens in hardware development is watching your team’s productivity slip because they’re forced into low-value tasks.

Agile philosophy teaches: Do only what creates value.

In PCB prototyping, that means minimizing recurring rework and cleaning up tool-induced errors. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly salary for electrical and electronics engineers was $57 USD in 2024. If a design engineer spends hours babysitting a pick and place machine or debugging a misplacement caused by poor soldering, it is a waste of resources.

The right pick and place machine is one that fades into the background — making the iteration workflow frictionless, so engineers can focus on solving meaningful problems, instead of playing whack-a-mole with machine settings.

Core criteria for a truly helpful pick and place machine

When evaluating pick and place machines for PCBA prototyping, teams should look beyond datasheet specs and focus on easy setup, workflow integration, and reliability.

Easy setup

While CPH (components per hour) dominates spec sheets, low-friction setup matter far more in prototyping.

An ideal pick and place should be easy to start, so that engineers can run multiple spins in a day. An intuitive interface and minimal manual steps ensure valuable time goes toward debugging real design issues, not configuring equipment.

Workflow integration

Prototyping should not be split across separate machines for placement, inspection, and solder paste dispensing. Each handoff adds delays, increases the risk of human error, and leads to unnecessary rework.

An integrated solution keeps placement, inspection (such as AOI), and solder paste dispensing under one roof, which shortens operation cycles, reduces friction, and keeps engineers in control of their process.

Reliability

Don’t get caught in a feature race. What truly matters is consistent, predictable quality. Failures often occur in mechanical and precision-critical subsystems, such as feeders, vacuum pumps, motion controls, or vision systems, leading to downtime and wasted cycles.

Evaluating user reviews and vendor reputation helps avoid common pitfalls, while responsive support ensures problems are resolved quickly and iteration continues without interruption.

Conclusion: Tools as enablers of agile hardware development

Agile hardware development demands that iteration is the engine of progress. You can’t win by getting a design perfect on the first try — you win by learning fast, iterating, and adapting. But that only happens if your tools support the loop.

A truly prototyping-ready pick and place solution is one that is fast to set up, integrates core workflow steps, delivers high reliability, and gives engineers back their time for design.

So as you evaluate pick and place machines, ask: Does this tool accelerate iteration, or does it slow us down? Because in hardware, agility is fragile and tool choice will either empower your engineers or stunt your progress.

Interested in learning more about PCB assembly? Check out these resources:

- Blogs:

Discover how Voltera is transforming PCB assembly with Alta, our new desktop pick and place machine designed to streamline in-house prototyping.

Check out our Customer Stories

Take a closer look at what our customers are doing in the industry.